A BOTANY OF VIOLENCE

Across 529 Years of Resistance & Resurgence

After 5 years of collaborative research and working through the COVID-19 pandemic, we’re proud to share our new publication with GOFF Books, A Botany of Violence. A small but dense format with over 300 original archival images spread across a visual timeline of five centuries, ending with two essays, the book weaves a revisionist history of the cinchona plant, global pharma, colonial extraction, labor exploitation, and resistance movements in the Central Andes.

Back cover:

From germ theory to plantation logic, this book tracks 529 years of global, colonial powers in the violent search for the elusive Cinchona plant of South America. Smuggled and stolen by the Jesuits and the Spanish Monarchy in the 17th century, transplanted by Britain and Holland in India and Indonesia during the 18th century, mapped by German explorer Alexander von Humboldt in the 19th century, weaponized by the U.S. in the 20th century, and monopolized by global pharma in the 21st century, the story of the Cinchona plant—the tree called ‘fever’—literally lies at the base of modern civilization. The quest to find the cure for malaria and to control the production of quinine as seen in the corporate monopoly in Africa today also traces deep roots of territorial dispossession and labor exploitation that lie between the Amazon and the Andes.

Behind the mask of heritage preservation and resource conservation, five centuries of graphic evidence put into sharp relief the uneven scales of racialized, gendered violence that are rooted in territorial injustices and underpinned by state nationalism. Bringing the map and the territory closer together, state-sanctioned policies of resource extraction and environmental destruction are interwoven with contemporary narratives of sovereignty and self-determination. Like a geopolitical treatise, the archival activism of this book rebuilds relations with the Cinchona plant, by reclaiming territorial histories of its peoples and its ancestral lands to confront the oppressive structures of the settler-state. Overlooked, suppressed, and marginalized, the long history of resistance movements and rebellions led by Indigenous and Afro-Latina women not only reveals the settler-colonial force of the nation-state. Their contemporary resurgence in the 21st century proposes a counter-map: a way challenge to the plague of violence and weaponization of resources of the past five centuries and its transformation into a regenerative flora of the future.

“From fact to fiction to fable, the scientific and taxonomic epistemologies of the Cinchona plant are rooted in longstanding forms of imperial conquest and economic appropriation, as well as cultural construction and scientific misinterpretation. And to be sure, the dehumanizing holism of German explorer Alexander von Humboldt’s hegemonic universalism, his trite naturalism, performative humanism, regional romance, equatorial fetish, and missionary lust lie at its very core.”

A Botany of Violence is available from the publisher, GOFF Books (an

imprint of ORO Editions), independent design bookstores worldwide, and all

major booksellers online. The book was reviewed by landscape scholar Rod

Barnett (Māori) in Places Journal (March 2023), “The Dog

Barks.”

A pre-launch of A Botany of Violence was accompanied by the exhibition and symposium Towards a Flora of the Future: An Initiative on Forensic Botany, Climate Activism, Territorial Justice, and Liberatory Feminism at University of Virginia School of Architecture in early 2022, following the launch of an online multimedia platform for the book & exhibition archive: floradelfutu.ro.

THE WRITING ON THE WALL

An Open Letter to Rem Koolhaas & the Guggenheim Museum

Initiated by a coalition of Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars from the Global South, this Open Letter confronts the curatorial team of Countryside, The Future to issue a public apology for the ignorant and racist claims to self-indigenization exhibited on the walls at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum between February 20, 2020 and February 15, 2021.

“Widespread throughout the exhibition and accompanying publication are several strategies of dispossession premised on extraction, erasure, and race-shifting. Not only are they the result of cultural extraction of traditional Indigenous knowledge, but their content is premised on the systemic erasure and evacuation of Indigenous Peoples, and the myth of white supremacy that presumes everyone at some point in time and place was Native. This is settler-colonial tradecraft.”

As a call to stop cultural appropriation, race-shifting, & self-indigenization, t

he contents of the letter

(including the online public petition)

released on January 17th, 2022 can be found online in English & Spanish: whiteskinwhitewallswhiteli.es

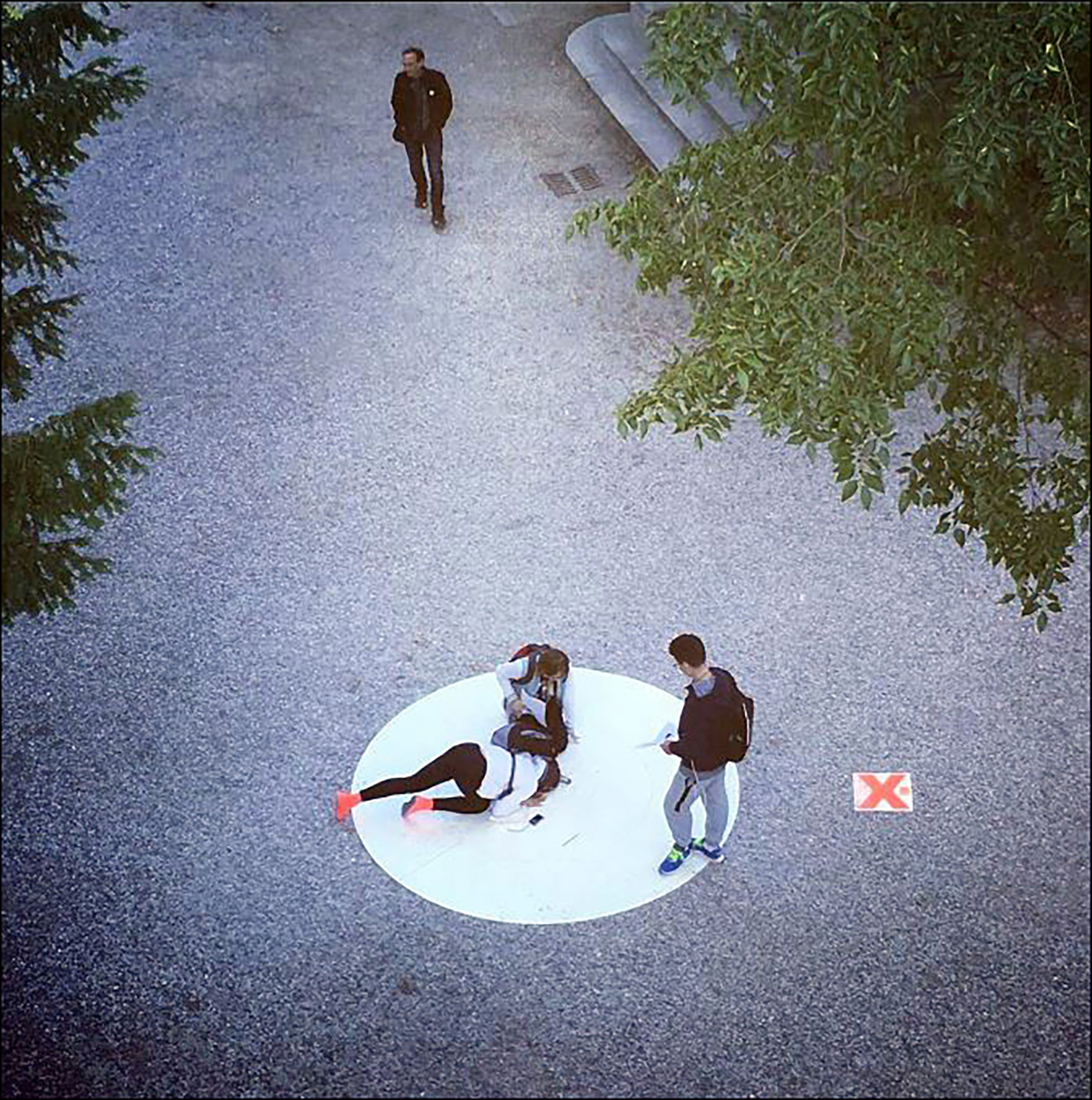

c.1993

Pretexts, Subtexts, Contexts in Struggles for Environmental Justice

In collaboration with students at Cornell University for the 2021 Landscape Conference, we brought

together writings from the past 25 years by authors, artists, and activists whose

work is dedicated to environmental justice. Retroactively challenging the focus

of design disciplines on the future, these essential readings (organized around the year 1993) focus on grounding design in

the present.

“this work of repatriation in the academy, is not about victimization or blame games. It’s about the acknowledgement and resolution of real and tangible crimes so that a future truly is worth living.”

From Kofi Boone’s “Black Landscapes Matter” (2020) and Rod

Barnett’s “Designing Indian Country” (2016), to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s “Land

as Pedagogy” (2004) and Deborah Miranda’s “Teaching on Stolen Ground” (2007),

as well as Austin Allen’s “Claiming Open Spaces” (1994) and Kimberlé Crenshaw’s “Mapping

the Margins” (1993), the compilation of multimedia texts challenge

the current historiographies, methodologies, narratives, and rhetorical devices of landscape architecture (and its allied disiciplines) as they have been taught since its foundation in the mid-19th century in

America and 16-18th centuries in Europe. The compilation purposefully confronts disicplinary histories that deny, erase, and actively suppress the

violence of settler-colonialism at the moment that lands & labor were being (and continue to be) stolen from nations and communities of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

Confronting struggles for environmental justice that

crystallized in the mid 1980s from the fallout of Anglo-American environmentalism in the 1970s,

the readings expose the complicity of settler-colonial heteropatriarchy intrinsic to and denied

the professions, disciplines, and institutions of design in preserving histories and maintaining structures of white supremacy.

“Almost alone among the key players of this century’s history, the landscape remains silent. But in truth it may be the most expert witness of all. In its broadest sense, ‘landscape’ is a stage on which struggles occur—where humans extract resources from the earth, suburbs drain people and wealth from cities, and territory is contested between warring groups. Landscape is also a kind of slate upon which the evidence of culture, habitation, and labor is written and may be read.”

If the fields of design are wholly and utterly unprepared for

the massive political change and demographic shift that is underway in this

generation, the lens of these authors offer up a core, spatial question for designers:

how can you change, shape or influence the future if you consistently

misunderstand and misread the present?

For an introduction by the curators of the c.1993 compilation, see “LANDSCAPE AS RESISTANCE: Pretexts,

Subtexts, Contexts in Struggles for Environmental Justice.” As bibliography, pedagogy, and curricula for this next generation of landscape architects, the entire compilation of downloadable texts and archive of viewwable media can be accessed through linktr.ee/c1993

EL TRATADO DEL QUINO

Renewing Relations

with the Quino Tree

at the Center of the World

by Decolonizing Quinine

& the Global Discourse

on Conservation

From germ theory to plantation

logic, this exhibition charts the 497-year legacy of global, colonial powers in the

violent search for the elusive Cinchona plant of South America in the cure for

malaria. Stolen by the Jesuits in the 17th century, smuggled abroad by Britain

and Holland during the 18th century, mapped by German explorer Alexander von

Humboldt in the 19th century, and exploited by global pharma in the 20th

century, the story of the Cinchona plant—and of its powerful quinine extract—not only lies at the base of modern civilization but traces the deep roots of

Indigenous, territorial resistance back to the Amazon and the Andes. Composed

as a geopolitical treatise, this initiative proposes a countermap to rebuild

relations with the Cinchona plant—originally known to its peoples as the “Quino

tree”—and to challenge territorial destruction and gendered violence that continue to increase

amidst state-sanctioned resource extraction, economic inequality, and benevolent conservation.

“Since the beginning of our life as a people, this territory has been our supermarket, our pharmacy, our hardware store. Our ancestors were born and buried here. Our connection to this place is deeper than the state’s. We should be managing it and protecting it.”

Produced by LA MINGA Collaborative, NOT YOUR AMAZON, and OPSYS Media, this initiative involves a program of events coming in 2021 and 2022 including an exhibition, publication, and conference that coincide with the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale in Italy (2021) and the Quito Pan-American Architecture Biennial (2022) in Ecuador.

CONFRONTING COLUMBUS

The Weaponization of Urban Space & Racialization of the Public Sphere in Boston

In a period of less than six months in 1979 at the height of federally-mandated school desegregation in Boston, a public park originally designed as a children’s playground and built with the intention of reducing social and economic inequalities, nearly three decades in the making between 1949 and 1976—with more than $60 million in federal and municipal funds notwithstanding the involvement of hundreds of people and diverse communities to open access to the water—was coopted by a small committee of private interests whose corrupt efforts resulted in the deceitful renaming of the park to edify a violent, genocidal killer and unsanctioned placement of a statue of that, since then, has fueled 40 years of racial division, historical deception, and socio-political confrontation.

See the Open Letter to Boston Mayor Marty Walsh to learn more about the lies and deception that took place in the hot summer of 1979. Launching a multi-year initiative The 1492 Project after more than 5 years of research, this letter comes with a 22-page Archival Resource Guide that comprehensively documents corruption of public process in the renaming of Waterfront Park and placement of the Christopher Columbus statue on October 23rd, 1979. An earlier story and tweet thread, “Confronting Columbus,” was posted online on June 12th, 2020 following the beheading of the Columbus statue on the night of June 10th, 2020, and its subsequent removal from the park, two days later on Friday, June 12th, to Shaughnessy & Ahern’s Warehouse in South Boston. A series of public hearings were subsequently planned over the next few months by the Boston Art Commission to assess what the Mayor of Boston has argued as the ‘historical meaning’ of the statue and park.

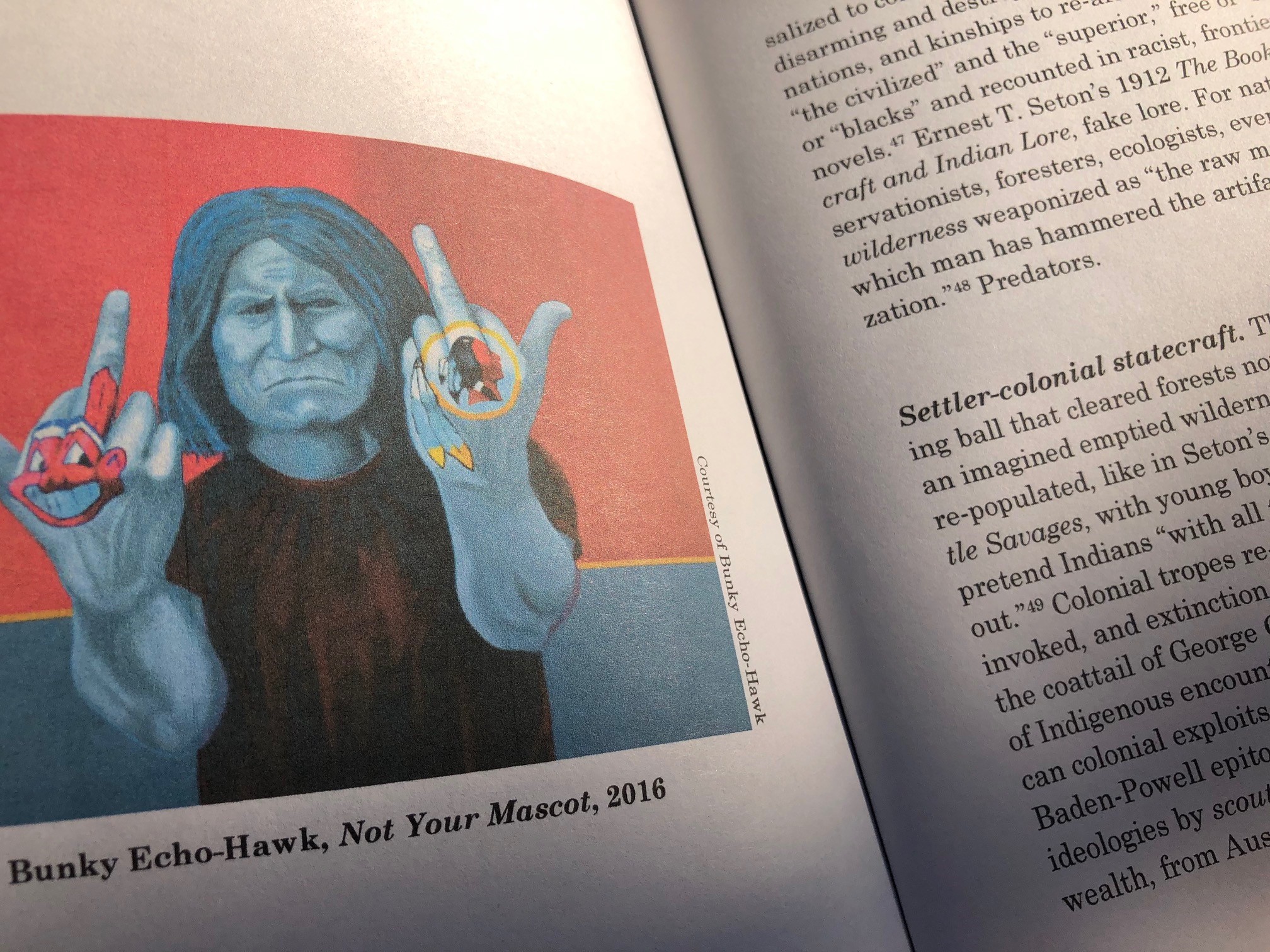

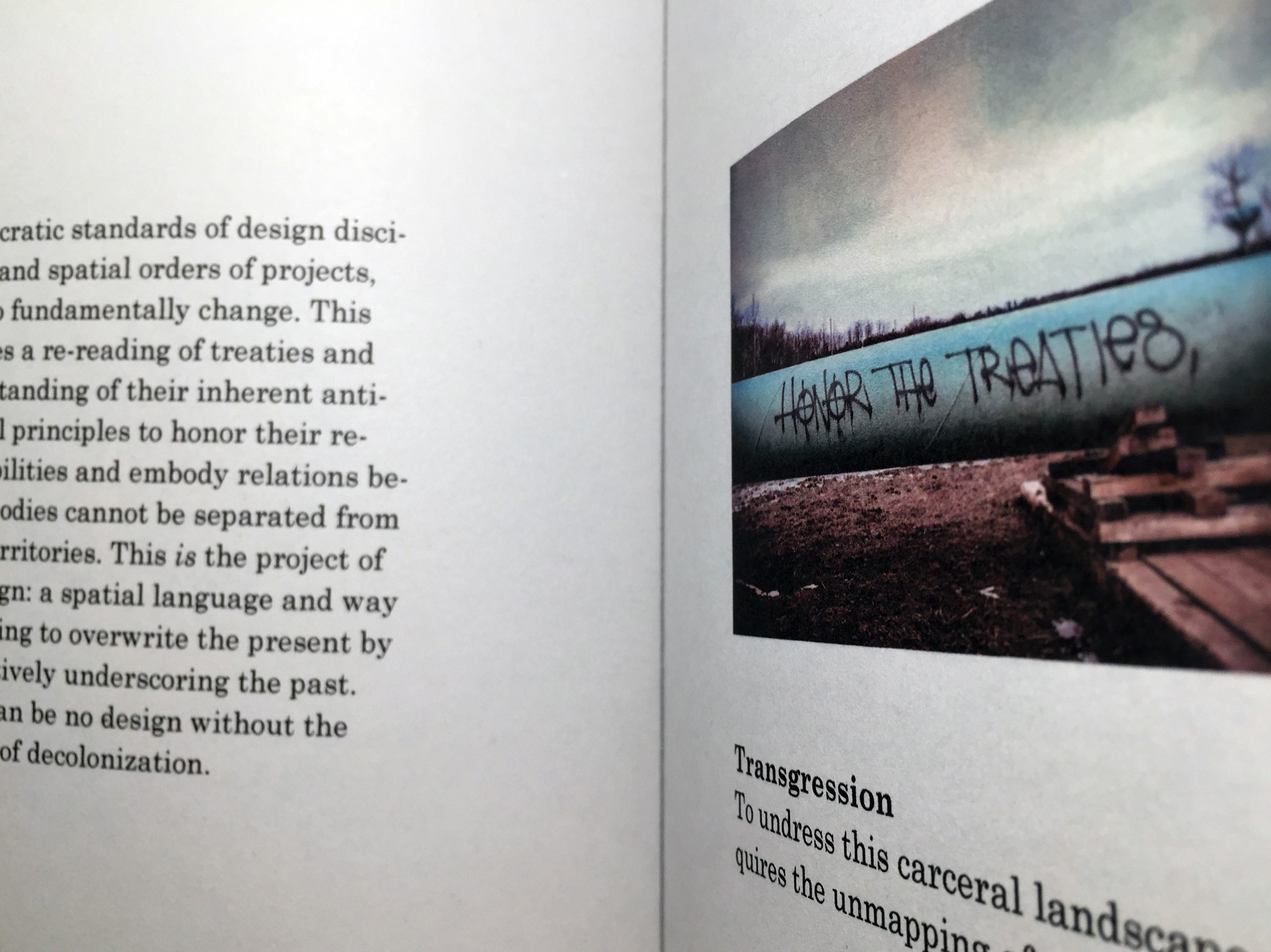

NO DESIGN ON STOLEN LAND

Dismantling Design’s Dehumanizing

White Supremacy

Every single building site – from a house to a highway – benefits from the exploitation of a capitalist property regime built on the back of broken treaties. These sites are not only taken from stolen lands and unceded territories, they are the spatial products of a violent structure and system of settler-colonialism that displaced and continue to dispossess indigenous peoples through more than 500 years of territorial injustices. Mundus Novus. Terra Nullius. Doctrine of Discovery. Manifest Destiny.

“...the oppressive system of settler colonialism is now normalised through contemporary urbanism, precisely because of the ‘denigration of Indigenous culture. Basically, it’s racism … systemic, institutional, individual, interpersonal racism.’ As Deborah A Miranda writes in Teaching on Stolen Ground (2007), ‘genocide depends upon the appropriation of the identity of the colonized by the colonizer.’”

This special edition booklet features a longform essay originally published in a January 2020 issue of Architectural Design (AD) Magazine titled “The Landscapists.”

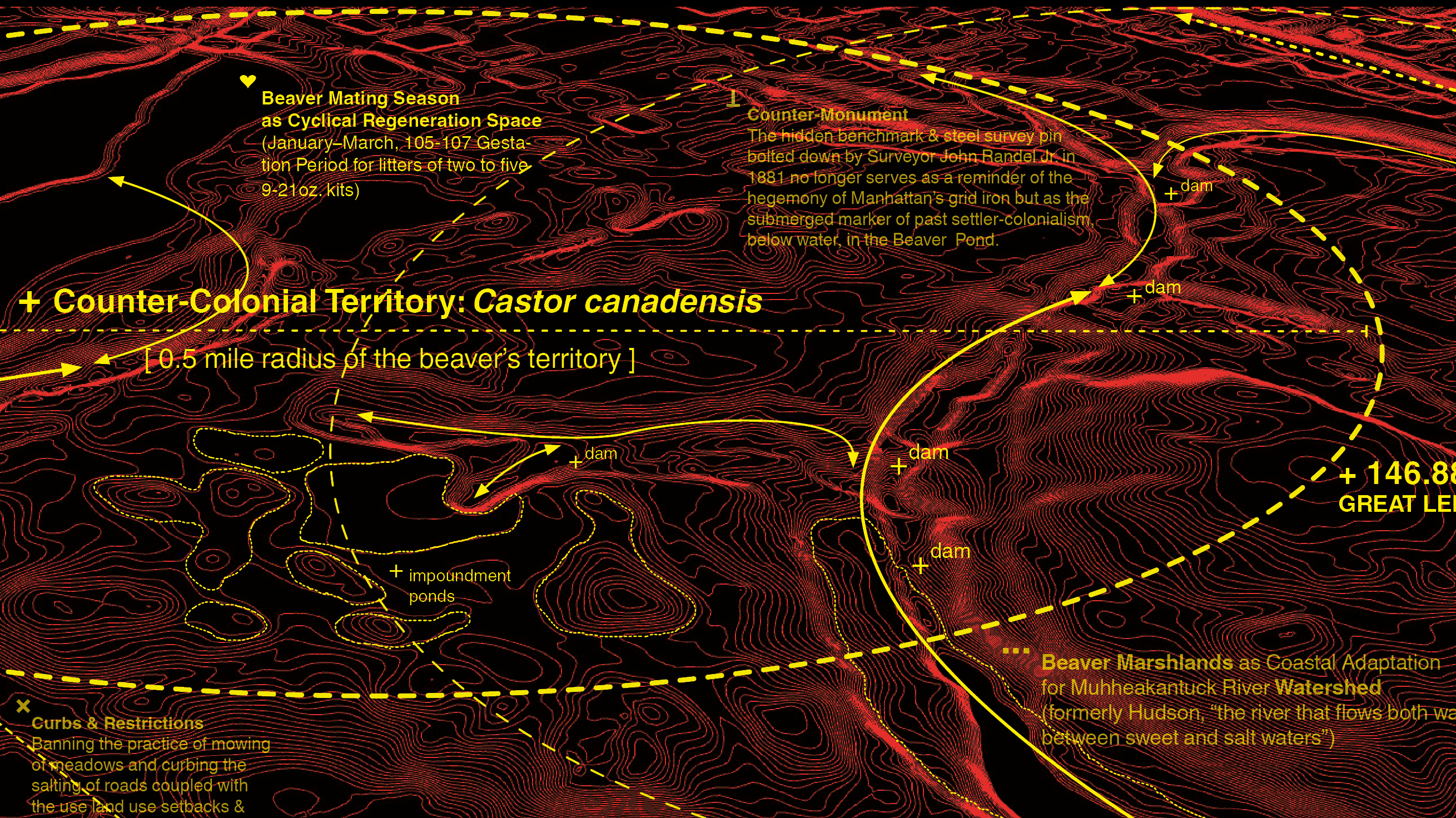

DAMN IT!

The Beaver Manifesto

A counter-colonial proposal for the site of Central Park as retroactive space for the unleashing of the beaver as the quintessential landscape architect of climate change for the 21st century. Here, Central Park—including its Victorian-era vestiges & racist monuments—becomes a boneyard of settler colonialism & blueprint for the imminent retrocession of lands of the Lenape-Delaware Peoples and the Indigenous territories of the once and future legacy of National Parks it camouflages.

“Central Park belongs no more to the City—either of New York, or of New Yorkers—than National Parks belong to the State—of America, or of Americans.”

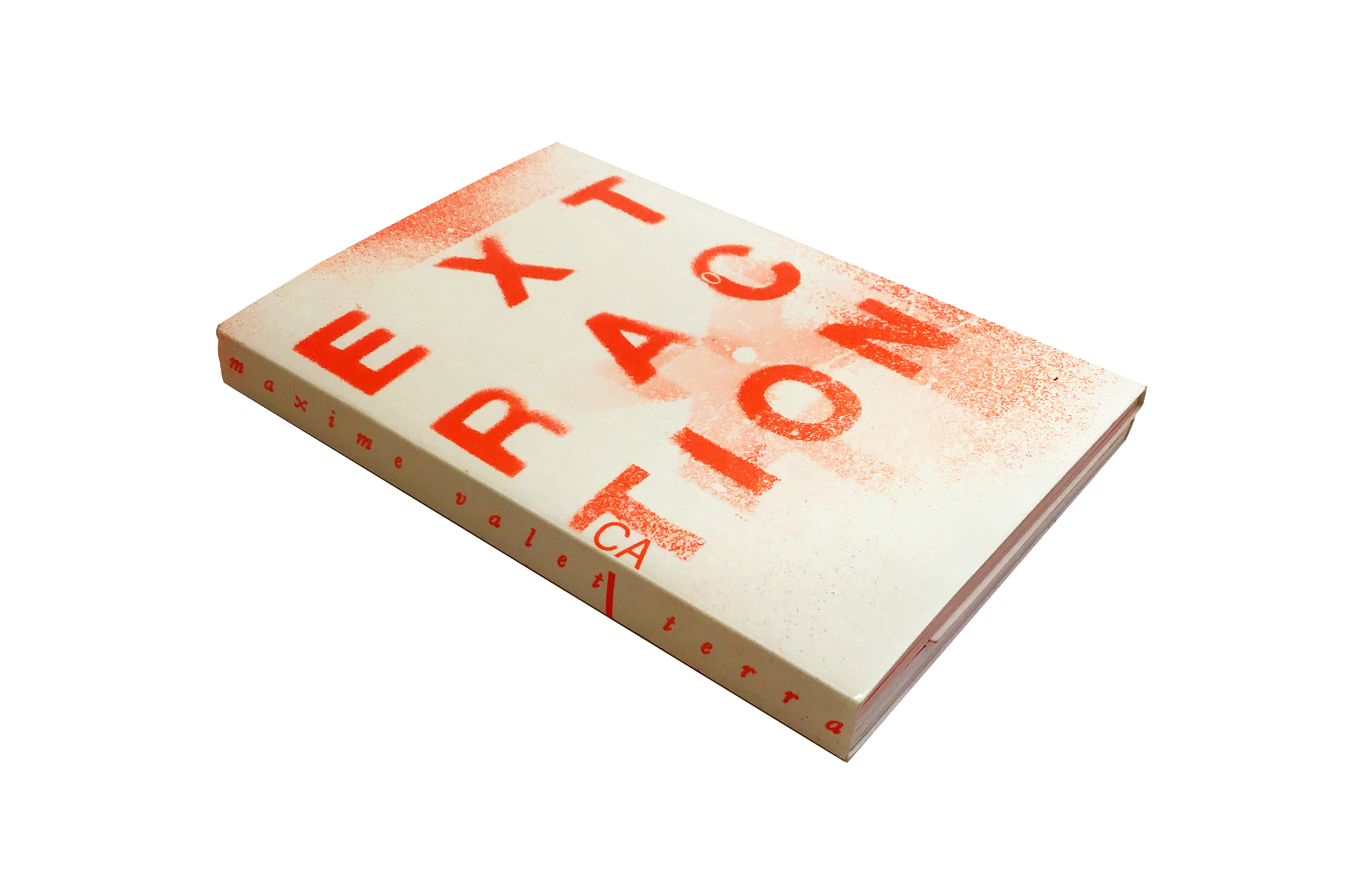

EXTRACTION EMPIRE

Undermining the Systems, States, & Scales of Canada’s Global Resource Empire 2017–1217

Extraction is the process and practice that defines Canada, at home and abroad. Of the nearly 20,000 mining projects in the world from Africa to Latin America, more than half are Canadian operated. Not only does the mining economy employ close to 400,000 people in Canada, it contributed $57 billion CAD to Canada's GDP in 2014 alone. Globally, more than 75 percent of the world's mining firms are based in Canada. The scale of these statistics naturally extends the logic of Canada's historical legacy as state, nation, and now as global resource empire. Canada, once a far-flung northern outpost of the British Empire, has become an empire in its own right. Published by MIT Press with funding from the Graham Foundation, this book examines both the historic and contemporary Canadian culture of extraction, with essays, interviews, archival material, and multimedia visualizations.

EXTRACTION @ Google Arts & Culture

See the permanent online exhibition of the making, research, team, collaborators, and the finale of EXTRACTION and the Canadian Pavilion at the Google Cultural Institute featuring an array of media and materials never before seen beyond the grounds of the exhibition in Venice.

VENICE

ARCHITECTURE BIENNALE

Opening a wider lens on the cultures of extraction, the project intends to develop a deeper discourse on the complex ecologies and territory of resource extraction. From gravel to gold, across highways and circuit boards, every single aspect of contemporary urban life today is mediated by mineral resources. Through the multimedia language of film, print, and exhibition, the landscape of resource extraction—from exploration, to mining, to processing, to construction, to recycling, to reclamation—can be explored and revealed as the bedrock of contemporary urban life. The Extraction Exhibition was part of the 15th edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale, with archive feed on Twitter and Instagram.

“Not only do imperial colonial powers redefine territories, they also breed new empires, replaying their cycles of dissemination and domination over and over again.”

—Suzanne Zeller, “The Colonial World as Geological Metaphor: Strata(gems) of Empire in Victorian Canada,” 2001

CANADIAN PAVILION in Venice, recognized & awarded by the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects, Azure Magazine, and the Ontario Association of Landscape Architects. Read the reviews by Robert Enright "What's At Stake" in Border Crossings Magazine, "Confronting our National Demons" by Fionn Macleod in The Walrus, and "The Limits of the Plan" by Maitiú Ward in Foreground Magazine.

NEW GEOGRAPHIES 09

Posthuman

This 9th issue of New Geographies Journal surveys the urban

environments shaping the more-than-human geographies of the early 21st century,

as well as spaces, systems, and scales of conflict, violence, and exploitation.

This interpretation is fueled by awareness of the historical instrumentality of

both geography and design (as disciplinary fields and spatial worldviews) in

the delineation and pursuit of new “frontiers” serving the ambition for endless

expansion of the human empire. With

this in mind, geographic and design thinking are here mobilized in a different

direction: namely, as an interpretive lens through which to trace how those

crises and historical circumstances that have destabilized the inherited schema

of the human manifest themselves spatially—how they are indexed by the complex

geographical formations of the contemporary built environment. Ultimately, posthuman

ask: where can sites of resistance and hope possibly emerge? NG09 is published by ACTAR with support of the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

“Settler States, former metropoles, and postcolonies are all hunted by the specter of colonialism—the geographic, architectural, epistemic, and historical framework of dehumanization, slavery, and extraction. Ruins and ruinations are spatial and temporal. In this epoch, they exist in the more the more-than-human and less-than-nature landscapes, and in the discourses on history and time deployed to justify, challenge, and make sense of them. … Here, the human is not the problem to move beyond. Like the dystopian ruins that has already been the fact of life for Indigenous peoples for centuries, it is a condition that must be inhabited and nurtured so that our voices can carry to the future.”

—Eli Nelson, “Walking to the Future in the Steps of Our Ancestors,” 2018

THE MISSING 400

On the Erasure of Women from the Urban

Environment

An open-source book produced in collaboration with Hélène Cixous. This book accompanies an 8-minute videographic essay that re-examines the institutional structures of sexism and historical roots of racism in architecture that have led to the systematic erasure of women from the design disciplines of the built environment. The multimedia project features a live diagram that maps out the names of over 800 women, whose lives—as designers, builders, writers, historians, photographers, philanthropists, and more—have shaped over 800 years of urban history. Narrated by Hélène Cixous, one of the most influential feminist authors in the world, with Ghazal Jafari. As part of this project, the original list of women compiled since its creation in 2016 has expanded to over 800 names and will continue to grow over time as a live document. An original performance of this project was staged with students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design on October 28, 2016. The content of the book is based on an original Open Letter written to Charles Jencks and published on October 7, 2016. The special edition of the book includes a poster that maps out the lives of over 800 women creators and shapers of the built environment across the past 800 years.

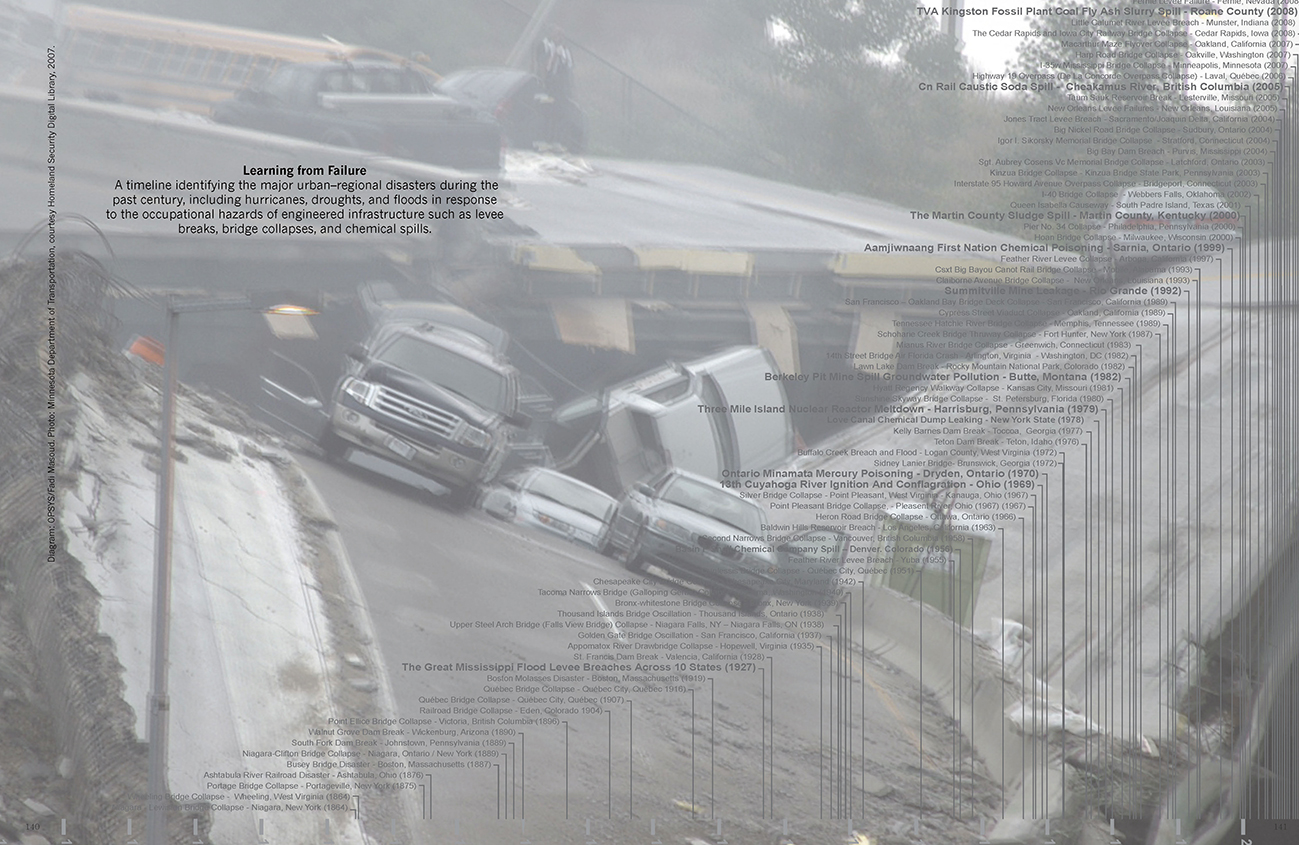

LANDSCAPE AS INFRASTRUCTURE

As ecology becomes the new engineering, the projection of landscape as infrastructure—the contemporary alignment of the disciplines of landscape architecture, civil engineering, and urban planning— has become pressing. Predominant challenges facing urban regions and territories today—including shifting climates, material flows, and population mobilities, are addressed and strategized here. Responding to the under-performance of master planning and over-exertion of technological systems at the end of twentieth century, this Routledge Landscape book argues for the strategic design of "infrastructural ecologies," describing a synthetic landscape of living, biophysical systems that operate as urban infrastructures to shape and direct the future of urban economies and cultures into the 21st century. See Gale Fulton's Book Review in Landscape Architecture Magazine. The book is originally based on a preliminary essay published in Landscape Journal.

“The outstanding feature of the modern cultural landscape is the dominance of pathways over settlements. … The pathways of modern life are also corridors of power, with power being understood in both its technological and political senses. By channeling the circulation of people, goods, and messages, they have transformed spatial relations by establishing lines of force that are privileged over the places and people left outside those lines.”

—Rosalind Williams, “Cultural Origins and Environmental Implications of Large Infrastructural Systems,” 1993

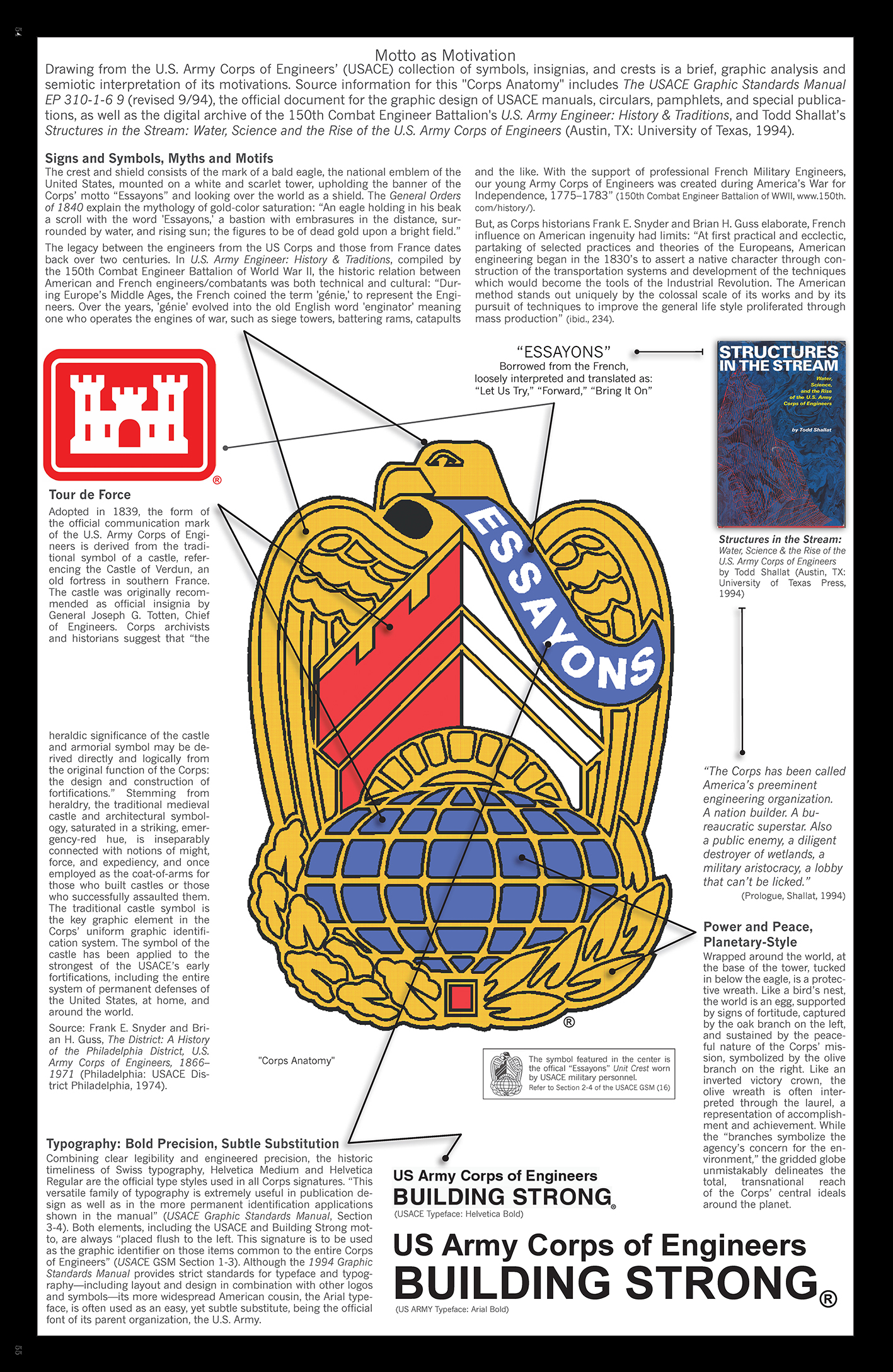

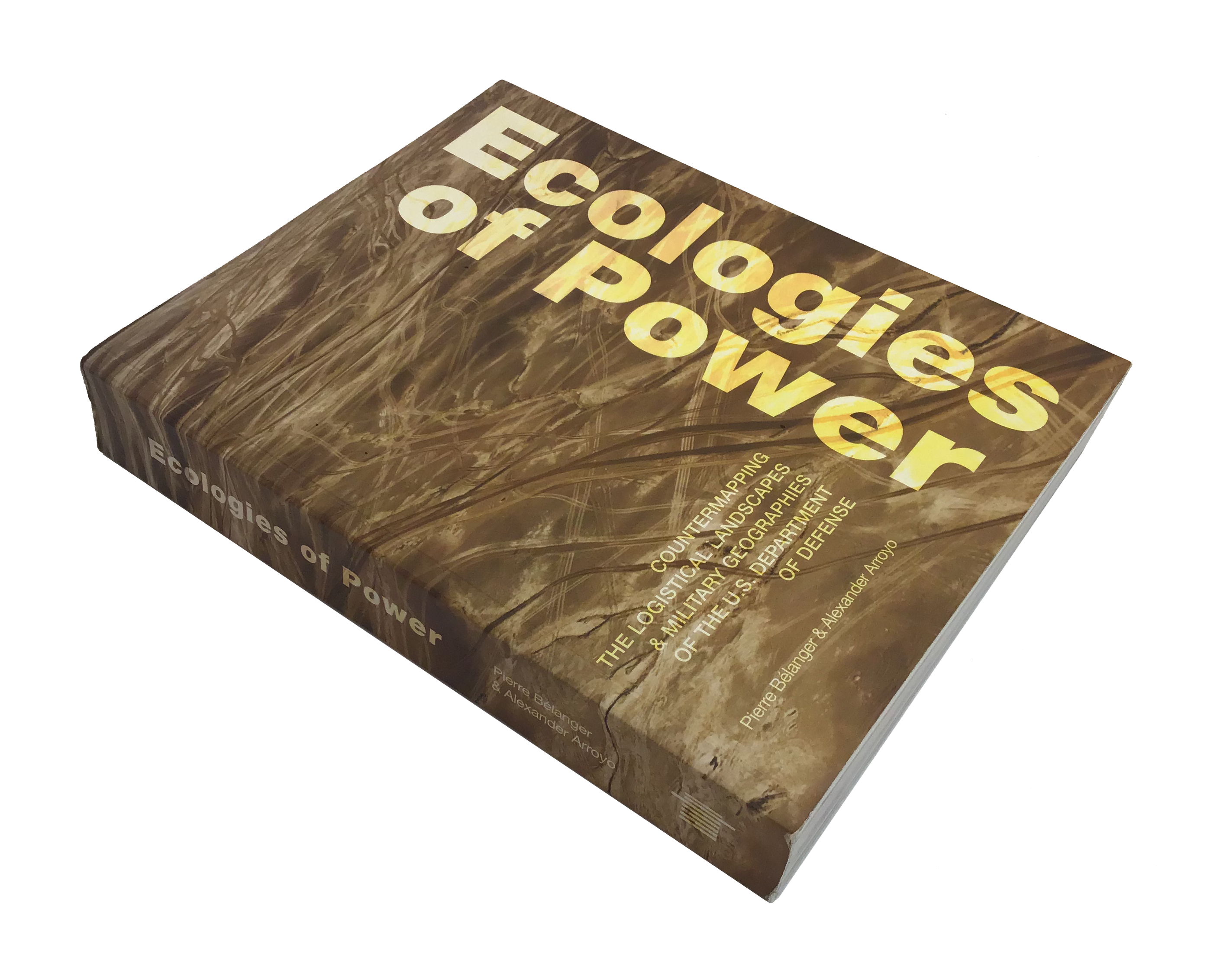

ECOLOGIES OF POWER

Countermapping the Logistical Landscapes and Military Geographies of the U.S. Department of Defense

This

book is not about war, nor is it a history of war. Avoiding the shock and awe

of wartime images, it explores the contemporary spatial configurations of power

camouflaged in the infrastructures, environments, and scales of military

operations. Instead of wartime highs, this book starts with drawdown lows, when

demobilization and decommissioning morph into realignment and prepositioning.

It is in this transitional milieu that the full material magnitudes and

geographic entanglements of contemporary militarism are laid bare. Through this

perpetual cycle of build up and breakdown, the U.S. Department of Defense—the

single largest developer, landowner, equipment contractor, and energy consumer

in the world—has engineered a planetary assemblage of “operational

environments” in which militarized, demilitarized, and non-militarized

landscapes are increasingly inextricable.

Through a series of critical

cartographic essays, the book traces this footprint

far beyond the battlefield, countermapping the geographies of U.S. militarism

across five of the most important and embattled operational environments: the

ocean, the atmosphere, the highway, the city, and the desert. From the Indian

Ocean atoll of Diego Garcia to the defense-contractor archipelago around

Washington, D.C.; from the A01 Highway circling Afghanistan's high-altitude

steppe to surveillance satellites pinging the planet from low-earth orbit; and

from the vast cold chain conveying military perishables worldwide to the global

constellation of military dumps, sinks, and scrapyards, the book unearths the

logistical infrastructures and residual landscapes that render strategy

spatial, militarism material, and power operational. In so doing, the book reveals unseen ecologies of power at work in the making and unmaking of

environments—operational, built, and otherwise—to come.

See the review by Rob Holmes at Journal of Architectural Education, Dr. Jack Adam MacLennan at Air & Space Power Journal, by Marion Clare Birch

at Journal of Medicine, Conflict and Survival, by Régine

Debatty at We Make Money Not Art, or by Christopher Kinsey at International Affairs. Published by MIT Press, Ecologies of Power is the recipient of The 2017 John Brinckerhoff Jackson Book Prize.

WET MATTER

The ocean remains a glaring blind spot in the Western imagination. Catastrophic events remind us of its influence—a lost airplane, a shark attack, an oil spill, an underwater earthquake—but we tend to marginalize or misunderstand the scales of the oceanic. It represents the “other 71 percent” of our planet. Meanwhile, like land, its surface and space continue to be radically instrumentalized: offshore zones territorialized by nation-states, high seas crisscrossed by shipping routes, estuaries metabolized by effluents, sea levels sensed by satellites, seabeds lined with submarines and plumbed for resources. As sewer, conveyor, battlefield, or mine, the ocean is a vast logistical landscape. Whether we speak of fishing zones or fish migration, coastal resilience or tropical storms, the ocean is both a frame for regulatory controls and a field of uncontrollable, indivisible processes. To characterize the ocean as catastrophic—imperiled environment, coastal risk, or contested territory—is to overlook its potential power.

The environments and mythologies of the ocean continue to support contemporary urban life in ways unseen and unimagined. The oceanic project—like the work of Marie Tharp, who mapped the seafloor in the shadows of Cold War star scientists—challenges the dry, closed, terrestrial frameworks that shape today’s industrial, corporate, and economic patterns. As contemporary civilization takes the oceanic turn, its future clearly lies beyond the purview of any head of state or space of a nation.

Published as the 39th issue of Harvard Design Magazine, Wet Matter reexamines the ocean’s historic and superficial remoteness and profiles the ocean as contemporary urban space and subject of material, political, and ecologic significance, asking how we are shaping it, and how it is shaping us.

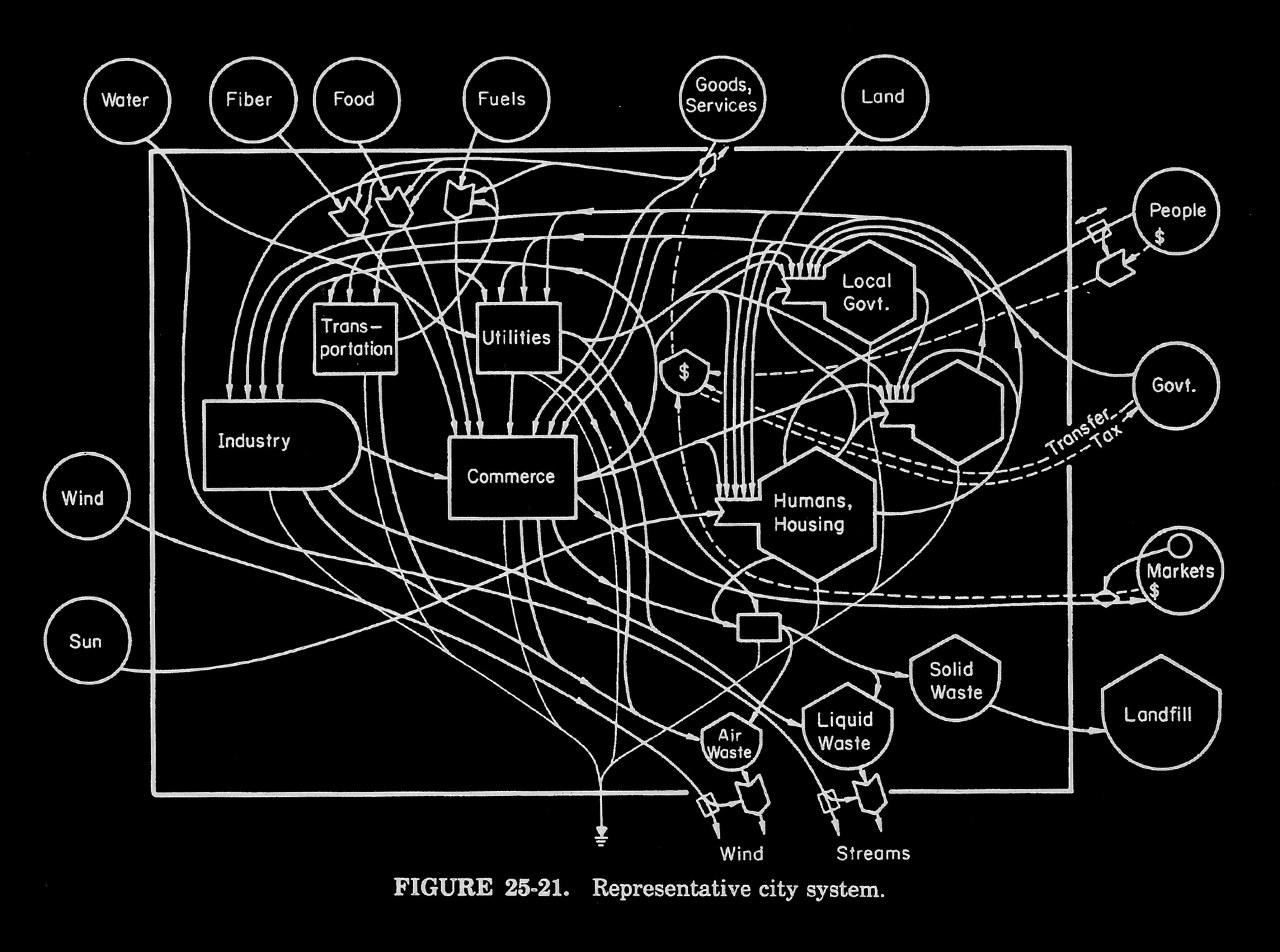

GOING LIVE

From States to Systems

If landscape is more than milieu or environment, and encompasses a deterritorialized world, then it is the contested territory, hidden actor, and secret agent of the twentieth century. Stemming from the early work of some of the most influential landscape urbanists–Frank Lloyd Wright, Ludwig Hilberseimer, Benton MacKaye, Patrick Geddes–this mini manifesto explores underdeveloped patterns and unfinished processes of urbanization at the precise moment when environmentalism began to fail and ecology emerged between the 1970s and 80s. Informed by systems thinking from the modern atomic age, this slim silver pamphlet takes inspiration from Howard T. Odum’s big green book A Tropical Rain Forest and brings alive the voices of a group of influential thinkers to exhume a body of ideas buried in the fallout of the explosion of digitalism, urbanism and deconstructivism during the early 1990s. Catalyzed by Chernobyl’s nuclear reactor meltdown, a counter-modernity and neo-urbanism emerged from the fall of the Berlin wall and the end of South African Apartheid. What happened during this concentrated era and area of change–across design, from architecture to planning–is nothing short of revolutionary.

GOING LIVE is published as the 35th edition of Princeton Architectural Press’ Pamphlet Architecture Series. Read Amelia Taylor-Hochberg's Book Review at ARCHINECT. Since the print version of the book is now out of print and only available through used bookstores, the original color version is now available online. For the backstory and the web supplement of the book, see pa35.net